Australia’s Resource Diplomacy Revisited as Minerals Deal with United States Draws Attention

Commentary reflects on Australia’s history of offering its resource wealth to allied powers, now mirrored in the recent rare-earths pact with the United States

Australia’s long history of anchoring its economic and strategic alignments on its abundant resource base has entered a new chapter following the rare-earths and critical-minerals agreement signed with the United States.

The pact, struck between Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and President Donald Trump in Washington, points to Australia offering access to its mineral endowments as part of a broader alignment with an ally.

Analysts trace this pattern back to earlier eras, noting how key Australian governments pivoted from Britain to the United States and Asia, always underpinned by exports of mining, agriculture and land-based wealth.

At the recent White House ceremony, Albanese emphasised that the two nations would “make more things together” under a joint pipeline of approximately US$8.5 billion aimed at mining, processing and refining rare earths—materials vital for advanced tech and defence.

Historical parallels are drawn to a 1915 agreement brokered by Attorney-General Billy Hughes during the First World War, which secured bulk contracts for Australia’s lead, zinc and copper production for Britain.

That deal enabled domestically rooted industrial growth and spurred a diversified manufacturing base.

Some commentators suggest that today’s scenario carries the potential for similar economic transformation—though not without risk.

The commentary argues that Australia’s abundance of mineral wealth and the political willingness to channel it into strategic partnerships places Canberra in a distinctive position—but also raises questions about the long-term nature of value capture.

While the recent deal emphasises that Australia wants more than just to be a quarry, critics caution that true value only emerges when refining, processing and advanced manufacturing co-locate domestically.

Indigenous land-rights issues and environmental legacy also form part of the discussion.

Ultimately, the piece invites reflection on whether this latest agreement will depart from past patterns—where Australia primarily exported raw materials—and instead anchor a “future made in Australia” strategy rooted in higher value-added activity.

The outcome could shape not just resource policy, but national identity in an era of global industrial competition.

The pact, struck between Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and President Donald Trump in Washington, points to Australia offering access to its mineral endowments as part of a broader alignment with an ally.

Analysts trace this pattern back to earlier eras, noting how key Australian governments pivoted from Britain to the United States and Asia, always underpinned by exports of mining, agriculture and land-based wealth.

At the recent White House ceremony, Albanese emphasised that the two nations would “make more things together” under a joint pipeline of approximately US$8.5 billion aimed at mining, processing and refining rare earths—materials vital for advanced tech and defence.

Historical parallels are drawn to a 1915 agreement brokered by Attorney-General Billy Hughes during the First World War, which secured bulk contracts for Australia’s lead, zinc and copper production for Britain.

That deal enabled domestically rooted industrial growth and spurred a diversified manufacturing base.

Some commentators suggest that today’s scenario carries the potential for similar economic transformation—though not without risk.

The commentary argues that Australia’s abundance of mineral wealth and the political willingness to channel it into strategic partnerships places Canberra in a distinctive position—but also raises questions about the long-term nature of value capture.

While the recent deal emphasises that Australia wants more than just to be a quarry, critics caution that true value only emerges when refining, processing and advanced manufacturing co-locate domestically.

Indigenous land-rights issues and environmental legacy also form part of the discussion.

Ultimately, the piece invites reflection on whether this latest agreement will depart from past patterns—where Australia primarily exported raw materials—and instead anchor a “future made in Australia” strategy rooted in higher value-added activity.

The outcome could shape not just resource policy, but national identity in an era of global industrial competition.

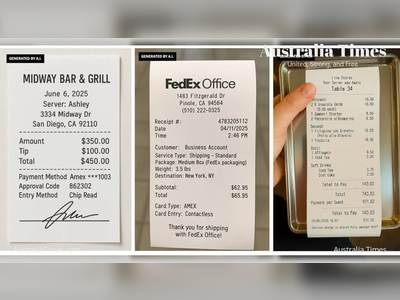

AI Disclaimer: An advanced artificial intelligence (AI) system generated the content of this page on its own. This innovative technology conducts extensive research from a variety of reliable sources, performs rigorous fact-checking and verification, cleans up and balances biased or manipulated content, and presents a minimal factual summary that is just enough yet essential for you to function as an informed and educated citizen. Please keep in mind, however, that this system is an evolving technology, and as a result, the article may contain accidental inaccuracies or errors. We urge you to help us improve our site by reporting any inaccuracies you find using the "Contact Us" link at the bottom of this page. Your helpful feedback helps us improve our system and deliver more precise content. When you find an article of interest here, please look for the full and extensive coverage of this topic in traditional news sources, as they are written by professional journalists that we try to support, not replace. We appreciate your understanding and assistance.